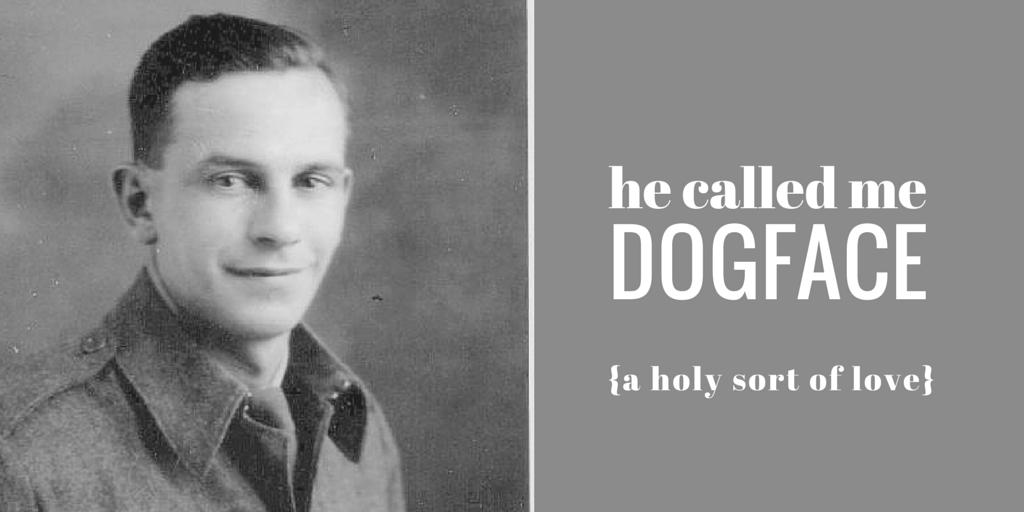

He called me Dogface.

No, really. He did. It was a term of endearment, I promise. A long-standing joke that wound through the years, connecting my grandfather and I.

“Get me some more tea,” he demanded one otherwise unremarkable summer day.

“How do you ask?” I replied, teasingly.

“Get me some more tea….Dogface”

And so it began.

That Christmas I found a holiday card in the shape of a dog. I peeled a photo of myself- early 90’s hot-rollered hair and short velvet formal dress- from my photo album. Afew snips of the scissors and a little glue later and my face smiled back at me from the Dalmatian-shaped card. I grinned to myself all the way to the college mailroom, imagining his face when he sliced open the envelope.

On break I traveled home and entered the house to find him – as always – holding court in the straight-backed blue chair by the door. He was clearly antsy with anticipation and I soon realized why. In the place of honor on the wall behind his head hung my card, now carefully mounted and framed, with a prominent BEWARE OF DOG sign carefully placed above.

And so it continued between my grandfather and I – a backand forth of teasing comments and practical jokes. Both of us amused with our cleverness and determined to one-up the other. I thought it would last forever.

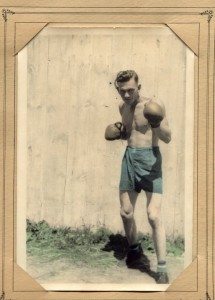

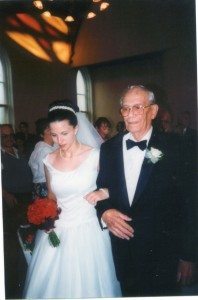

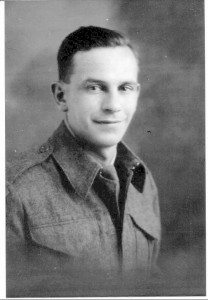

He was immortal, I believed. Ten feet tall and bullet proof. Sure, we worshiped super heroes and celebrities, but if you asked my siblings, cousins and I to list our heroes, his name always topped the list.

From him I learned political theory and a fierce sense of justice and the importance of always speaking my mind. That innate intelligence and good old fashion common sense outweighed formal education, but to grasp tight to every single opportunity to learn, classroom or not. I absorbed his commitment to community and society. I knew, with a depth that can only come from witnessing something for a lifetime, that family – always and forever – comes first, last and always and is the common thread that winds through everything else.

My concept of romantic love came from the way he loved my grandmother, as if the sun rose and set on her smile. My understanding of home and the value of knowing where the ground was solid beneath my feet came from the unwavering depths of his connection to the land that sheltered my childhood summers. My understanding that smart was good, but good old-fashioned hard work was better was absorbed from the work ethic he embodied. We learned to dig potatoes in the rich earth, and turn rough wood into swords and boats in the workshop, he’s the only one who could manage to teach me to parallel park well enough to get my license. Every single weekend of the summer The Saturday Night Party found us gathered in the living room, Granddad ensconced in his blue chair – reigning patriarch of a family who loved him like no other.

My grandmother, the constant glue that kept it all together, gladly took the supporting role and gave him center stage. It was his pride we sought to attain. His laughter we worked to provoke. The measure of anything we did or undertook, created or achieved was what Granddad would think. His opinion was primary and his satisfaction with our achievements outweighed all other rewards. Not a word of this is an exaggeration, and not an ounce of our devotion was misplaced.

***

Months later a package arrived at the small one bedroom apartment that Sam and I called home. It was curiously lightweight and marked by his familiar black scrawl. I remember looking up at Sam quite confused,

“It feels empty. I wonder what on earth it could be?”

He laughed and replied. “It’s a big ole box of Dogface, of course”.

I chuckled and rolled my eyes at what I thought was a lame joke, tearing into the brown paper wrapping with the enthusiasm of a child who has never gotten over the mysterious thrill of the postman’s delivery. And when it was open all I could do was laugh out loud. He was right. Of course he was. It was a big ole’ box of Dogface, after all.

The package contained small soft doll, of sorts. With the body and clothing of a witch, a studded collar encircling her neck, the gift might not have made sense were it not for the hard plastic dog head that was perched on top.

My grandfather, living in an 81 year old body ravaged by ageand by cancer and heart disease, had retained enough of his inner mischief to cook up this scheme. Purchasing a child’s doll and a rubber dog toy, dismantling their pieces and stitching them together to create the pièce de résistance in our ongoing game.

“Brilliantly played,” I told him when we next talked, imagining the great glee he must have taken in the orchestration of this. I immediately began trying to come up with a way to top him.

I never got the chance. He was taken to the hospital about a half hour from home. I remember talking to my aunt and agonizing about whether or not I should make the very expensive trip home.

“You’ll know when it’s time”, she said softly with the resolve of one who has faced loss many times, “you’ll just know”

And I did. I knew. And mere days later I was flying back home. Leaving the warm, dry desert and returning to a province blanketed in the thick snow of deep winter. And I found the most vibrant, vital man I had ever known lying in a hospital bed, unable to muster the strength to speak more than a few words. His clan had gathered, as we always did, around him. We occasionally fell silent and he would motion with his hands as if to encourage our voices to surround him still.

I was in denial. He would recover, and return home to white Dutch Colonial with the bright blue trim that he – a Canadian country boy – had built for his young American wife shortly after they were married. The home where she had birthed their children and together they had raised their family. The home where we had learned all that we ever needed to learn about roots and family and love. Of course he would return there – and be there always. How could this not be true? There was not even room in my heart for any other possibility.

The night before the very last my younger brother and I took our shift with him while everyone else went home. That night we watched a man with more dignity than any I have known before or since accept our love, even when it meant that we supported him while he went to the bathroom. We knew, even in the moment, a kind of hallowed and humble gratitude for the gift of that sleepless night. For a long time I held on to every word we exchanged but now – trying to write of them for the first time, I find that the edges are fuzzy, and cannot be captured on this screen. What I do recall was the privilege of being able to bear respectful witness to this man as he bore the collapse of his body with profound grace and solemn dignity.

The night that was to be the very last was a night of snow. Heavy and white, it blanketed everything. Howling wind and drifting high, until it was finally quiet; muffling sound and suspending time as we lived the life of palliative care, deep within the small country hospital. And we were all there, very nearly. Moving in and out of his room and the family room nextdoor. Eating and curling up together, giving love to him, and to each other as we all breathed the half-formed breaths of those who waited for the inevitable.

But still, I didn’t believe. Didn’t really understand. Didn’t want to know. Couldn’t comprehend that we were in the final stages of our dance with a man who had claimed every last moment of his life as whole and solid and his to have and experience fully.

For hours it was the same. Same quiet hushed tones. Same cycles of in and out. Same sharing of memories and quiet laughter and held back tears. Same knowledge of the precious gift of this, of our connection, of what we had been given.

It was all the same until it wasn’t, and as his breathing changed so did our energy. Somehow we all knew. Were all called back to his bedside without anyone saying a word. And we surrounded him and filled that space. Fully present with our bodies and hearts and souls and memories and gratitude and love.

My family encircled his hospice bed. All of us. His children. His grandchildren. His beloved wife. Together we spent our last moments with the man who had built us, a family of uncommon closeness. A man with a life force so strong and vital that it filled the room and also filled my heart and lungs and soul the way it had always filled my life. And we spent his last moments the way we had spent so many moments with him – together. Hands tightly clasped, arms around one another, we stood guard and witness as his spirit left the room.

This, twelve years later, stands as one of the only experiences of my life that I can name as Holy. Where life balanced on the cusp between the physical universe and what exists beyond our comprehension. There was a presence in that room that cannot be named or measured, and perhaps it was only what love feels like when magnified and crystalized by that sort of devotion. Perhaps that sort of love is always Holy – it’s just that we don’t remember to stop and pay attention until a moment of irrevocable magnitude causes us to pause and open wide enough to take it all in.

Yes, it has been twelve years since that stormy night that changed everything. And still, I remember him with an immediacy that proves to me that death is not an ending, not in the face of that much love. It’s only a continuation really, of what has been taught and learned and lives in us always.

And still, they call me Dogface sometimes, their voices an echo of his teasing tone, their faces bearing traces of his lineage. And I don’t mind. It keeps him close to me.

***

We were digging through a crate of old memories last year. Shoeboxes of letters from college roommates, concert ticket stubs and tattered photographs of old boyfriends. Journals with youthfully loopy handwriting chronicling days long past. “Mama, It’s like a time capsule of your life,” said my wee girlie, as she lifted bits of the flotsam and jetsam of my past from the depths of the bin. And then there was Dogface. Face cracked, limbs torn but still containing every ounce of his humor and love. And I picked up that raggedy doll and held it close as tears came to my eyes and I remembered.

Yes, he called me Dogface. And yes, it was a term of endearment. I promise.